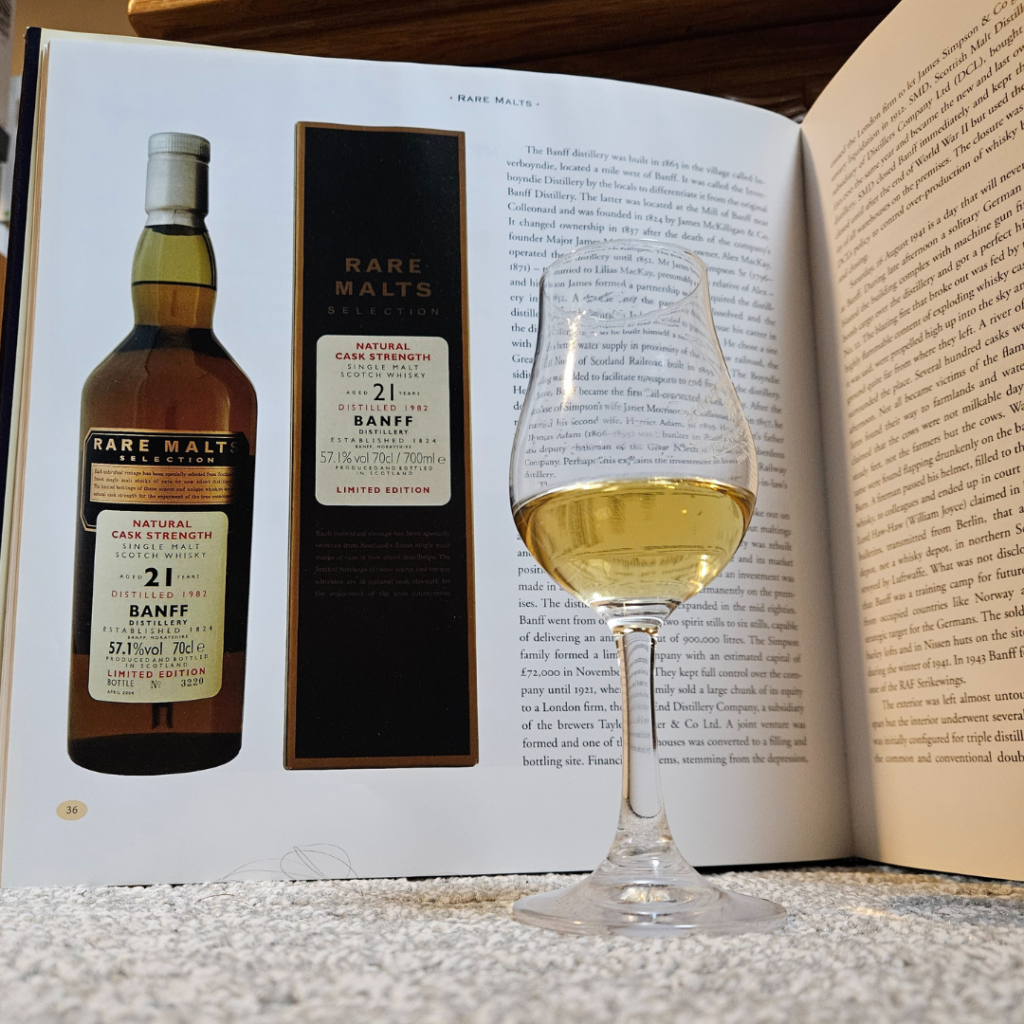

Banff 1982: a truly unique Rare Malt if there ever was one

In cooperation with expert whisky retailer Best of Wines, in the next months I will publish blogs about expressions in Diageo’s legendary Rare Malts Selection. This was a series devised to highlight the more obscure malts in the company’s portfolio, long before the interest in single malt whisky rose to its current day status. We indeed got very rare examples of lost distilleries (Port Ellen), unknown ones (Mannochmore) and regular ones at deviant ages (Clynelish). In one form or another, 121 versions were released. Today we continue our journey through liquid history with a truly unique expression of the Banff Distillery that was once located near the city of the same name, but actually in Inverboyndie. Be sure to check out our previous blog about Glenury Royal and St. Magdalene Distillery.

First point of entry for writing about whisky and the numerous brands out there, is surfing over to the Whiskybase and check what is there. The Banff Distillery has a meagre 180 entries in total, and surely not all of them are originating from the distillery itself, but use the name Banff in one way or another. If we check on proprietary bottlings, the result is even more scarce, with only four known bottles. And to top it off: the only 1982 Banff that is listed in the Whiskybase is the one we will taste today! Talk about your rare whisky, this is truly a unique one. We have to thank the independent bottlers for putting their casks into bottles, notably Cadenhead, Duncan Taylor, Douglas Laing, Signatory and Gordon & MacPhail. Banff would have been even more obscure!

What makes 1982 so unique to Banff? I have no idea. Obviously, Banff is one of those distilleries that got mothballed and closed in the famous economic downturn of the 1980s, which saw other facilities like Port Ellen, Brora and the three Inverness distilleries shut down, to name a few. But why no other casks from that year have hit the market; one could only speculate about that. Banff has a history of being used as a single malt, most famously for the House of Commons in Scotland. In general the output was used for blending purposes.

Those last casks produced in the early eighties may well have been put into bottle with lots of other malts and grains, to be poured in a cola eventually. In his standard work about the Rare Malts Selection, writer Ulf Buxrud mentions the blend Slater Rodger. I could not find a particular whisky named like that, but there was a company called Slater, Rodger & Co. Ltd. That was probably it then.

Banff has a history that could easily be made into a Netflix series, or could have been written by Gabriel García Márquez. The things that happened were all but fiction, however. Let’s move through the ages chronologically. The distillery was located near to the town of the same name, that was an important harbour at the North Sea and on the banks of the River Deveron. Other distilleries in the region that are active till this day are the Macduff Distillery and, more to the west, the Glenglassaugh Distillery. Banff itself was located in the small village Inverboyndie, and first built in 1863. In the beginning it was actually known as the Inverboyndie Distillery as there was a “Banff” in the region before the one we are speaking of now. (The bottle actually maintains the year 1824 as the year of establishment of Banff.) The new location of the distillery was strategically chosen, as it had access to good water and proximity to the Great North of Scotland Railroad that was built just years before. Banff had its own siding and actually became the first rail-connected distillery. Good question for a whisky quiz!

The first of many devastating events to strike at Banff happened in 1877 when a fire destroyed most of the distillery with only the warehouses and maltings saved. This happened in May, but the distillery was up and running again in October, so no big loses were felt. Banff invested in its own fire precautions that were kept on site permanently. In the meantime, Banff kept expanding, from one wash and two spirit stills to double that amount, so six stills. But soon, around the turn of the century, economic downturn took a hold on the Scottish whisky industry. At the end of all this, the original owners the family Simpson, went into voluntary liquidation in 1932. This is when Scottish Malt Distillers swept in and bought the distillery, only to close it down until after the Second World War. In this terrible time for the world, Banff was momentarily in the headlines of the news, especially in Germany! When German fighter planes bombed the location on 16 August 1941, they thought they had hit a massive weapons facility. Warehouse 12 indeed gave a fireball you could see on the moon probably. The stories are famous. Litres and litres of maturing whisky streamed into the nearby burn, giving all kinds of animals a hangover to make a movie about. On record, it is known that one fireman filled his helmet with whisky. He ended up in court for pilfering, even though I do not see the harm; he shared the whisky with his colleagues. Bottle sharing (or helmet-sharing) was still frowned upon in those days, I guess. In any case, the Germans thought that made a significant impact, and how ever much the loss of whisky is to be mourned, at that point the distillery was quite harmless. In later war years, that would change, as the location became a training location of the RAF.

Returning to regular distilling duties after the war, we saw some expansion. Banff already retired the original triple distillation regime in 1924 and went on to double distil the output. The intermediate still was removed. But there was no gentle purring going on, as a remarkable explosion made the news again in October 1959 when repairs were done on the spirit stills. The damages required a month’s work to repair. In the meantime, Banff also abandoned coal firing underneath the stills and replaced it with mechanised stoking. Even though the distillery kept growing and warehouses were added, it was finally closed on 31 May 1983. There have been plans for a replacement distillery, and permissions were granted twice, but nothing ever came of it. Today, all buildings are gone, and not even the unique King of Nailsworth mill remains. It seems that this was the only mill of this kind used in a Scottish distillery, so there, another feat you can add to the whisky quiz list.

Banff 1982, 21 years old, bottled at 57,1 % abv

First things first: Bottled in April 2004, so this Banff is probably very close to being a 22 year old. Like usual, there is no information on the cask makeup. Judging by the colour of the liquid, these were very light (refill?) bourbon casks. We know that at the end of Banff’s production period, the barley varieties Golden Promise and Triumph were used. Banff was one of those distilleries that used worm tubs in their production method. Some of the production was still malted by hand.

Upon Sipping: Knowing that expressions in the Rare Malts Selection need time to open, I always pour a glass and start writing the above text. The fragrant smell of this Banff distracted me quite a many time during my work. This whisky speaks loudly, and that is a nice change of scenery for the sometimes difficult RMS! Lots of vanilla swirling in the room here, a hint of smoke too, and something that reminds me of an IPA. Dry weeds, barley, uncut grass in the backyard that desperately needs to get done. Quite lively and floral. There is a hint of nail polish remover too. A whisky to have a nice rumble with!

Time for an undiluted taste now. Wow, I am amazed and delighted by how oily the palate gets. As if I accidentally took as bottle of massage oil and took a sip from that. The taste is grassy, with lots of creamy vanilla and a firm nuttiness.

I am reminded of a Fino sherry influence, which makes me doubt if not a few sherry casks ended up in this recipe, be it very, very refill in nature. The finish offers the hoppy beer taste that I usually associate with Banff, from the examples I have tasted in the past. It is interesting how this whisky develops from a waxy, quite farmy single malt into a character that seems more industrial towards the end. Let’s put in some drops of water.

Oh yes, the whisky blooms even more beautifully open now, with whiffs of vanilla and now even some honeycomb and candle wax. Dry hey on a summer’s day, careful not to drop a spark in here! You can notice it already smouldering a little. Somewhere in the distance you can also detect a hint of soft French cheese. Not disturbing, but I do not wish to enlarge that note, it might outstay its welcome. On the tongue, the vanilla is extremely strong now, and the beer note enlarged at the same time, which I do not care for too much. Playing with the pipet is really delicate here. You easily slip over the edge. With a good dash of water, I must admit Banff does turn nicely silky.

Word to the Wise: This Banff has redeemed itself over the years, and I admit this is due to my palate, not the way this Banff was made. Fact of the matter is: this is now a style so totally extinct in the spectrum of whisky these days, that I love it more than ever before. I tasted this particular expression blind in April 2018 and now I have tasted the remains of the sample I had that day. The almost 7 years in the sample bottle definitely mellowed the fierceness of Banff, and turned it into a shining jewel. I would like to challenge the whisky makers of today: try making a whisky like this again. You need only a few aspects: obedient wood, fill the cask at distilling strength (so not 63,5 % as has become standard now) and leave it alone for at least 20 years. Then one could recreate this Banff. Future generations will be as baffled as I am today.

Score: 89 points.

Geef een reactie